Some Parenting Practices With Your Adolescent to Consider

Because of the variety of cultures, circumstances, individuals, and families, there’s no one set of positive parenting practices for raising adolescents that works for everyone in every situation.

However, while this diversity rules, I believe a common goal of these practices is the same: to help parents stay caringly and influentially connected to their teenager as adolescence grows them independently apart, as it is meant to do.

With the proviso that no one approach is going to fit all, what follows are a few practices observed over the years that may (or may not) have helpful value. By no means an exhaustive list, and in no particular order, what follows are a few you might consider.

Use Operational Language: When declaring your needs and wants, stick to talking about specific behaviors or events, and avoid abstracts or generalities. Telling your teenager she is not acting “responsible,” for example, does communicate disapproval, but does not specify exactly what you are objecting to. Better to “operationalize” communication (see John Narciso, “Declare Yourself”) by describing what the young person is actually doing or not doing that causes you to use that disapproving term. Clearer to say: “When you make an agreement with me, I need to have you keep it, just as I keep my commitments with you. I consider honoring agreements to be responsible conduct, and I need for us to talk about that.”

Treat Conflict as Communication: When in disagreement with your adolescent, treat him as an Informant, not an Opponent. Conflict does not have to be a hostile exchange. Rather than respond to conflict as a challenge to your authority, or as a contest to win, treat it as a chance to better understand your adolescent’s thinking and feeling, and for you to be better understood. Then with this fuller mutual understanding try and craft some resolution – maybe to make some change, maybe not. “I want to hear what you have to say about the issue between us, I would like you to hear what I have to say, and in making my decision I will remain firm where I have to, but will be flexible where I can.”

Bridge Differences with Interest: Rather than criticize an unfamiliar difference in your teenager, ask for help in understanding it. Adolescence is a journey into unfamiliar life territory where the young person will experiment with many new interests and beliefs in the course of growing up. Most of these will be of a trial and not terminal in nature. (That style of dress will not last forever.) To ignore or criticize the difference only turns it into a barrier separating the relationship. Better to make it a bridge for connecting you both by expressing interest and requesting some education. Now a powerful role reversal can occur. You being the student and your teenager being the teacher can be an esteem-filling experience for the adolescent. “This computer gaming is totally outside of my experience. You're more expert here. Can you explain and show me a how it is played so I can better understand?”

Empathetically Relate: Try walking in the adolescent's “shoes of life experience” by feeling how she may be feeling. Call this empathy or emotional outreach or sensitivity, but the expression of this felt response to the adolescent’s feelings can be powerfully connecting. When the parent says, “If I had the experience you just described, I would be feeling angry too,” the adolescent feels accepted, supported, and not alone. Keeping her emotional company keeps parent and adolescent close during a hard time. “I felt that my mom really knew what I was going through. She was really there for me.”

Mean what You Say: If you want something from your adolescent enough to demand or ask for it, then follow through with enough supervision to see it gets done. In adolescence there is often more passive resistance to the requests of adult authority. The young person often finds that if he delays compliance to a parental request long enough, parents may forget or give up or do without or even do themselves what they were wanting. Thus when parents fail to pursue what they ask, they can undermine their efforts. To the adolescent, this inconsistency shows that sometimes they mean what they say and sometimes they don’t. Given this double message, the adolescent is likely to vote for “don’t.” Better for the adolescent to trust the parent's word: "When my mom makes a rule or a request, I know she means what she says."

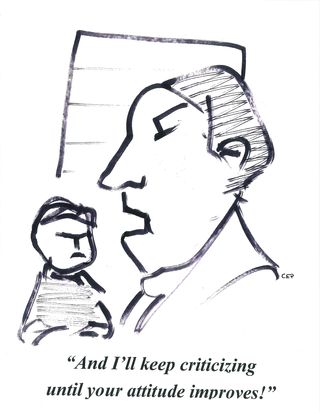

Use Non-Evaluative Correction: Take issue with the adolescent’s choices for misconduct, but don’t judge or criticize their character. When parental correction is coupled with personal criticism it tends to be disconnecting. "When my dad starts putting me down, I stop listening to what he has to say." Better for parents to be more objective and focus on decision-making only. “We disagree with the choice you have made, this is why, this is what we need to have happen now, and this is what we hope you learn.” Correction that has lasting educational value is usually criticism-free.

Give a Hearing: Let the adolescent have a full say about what matters to them, especially when in disagreement or in dissatisfaction with you. Because adolescents are more often inclined to be oppositional to parents and because parents are often more inclined to oppose some freedoms the adolescent wants, it’s easy for frustration on both sides to get in the way of getting along. Sometimes, teenage acceptance of an unpopular parental refusal or request can be made easier for a young person if a common compromise is made. When parents respectfully allow the adolescent to have her say, they are often more likely to be given their way. So the young person explains: “Even though I didn’t get what I wanted, at least they cared enough to hear me out.”

Listen at the Time: Because adolescent self-disclosure depends on psychological readiness, pay attention when the adolescent wants to share. The teenager who says, “I don’t feel like talking about it right now,” isn’t lying. Openness to speak about personal issues depends on being in the right mood or emotional place, which may prove a bad or inconvenient time for the parent. Thus, when the teenager is tired enough late at night to talk about the hardships of her day, the tired parent who hungers for sleep stays awake to hear. The parent knows that putting off adolescent confiding until another "better" time means missing important communication. The mysterious openness for personal sharing will have passed. So, when it comes to listening, parents need to seize the moment.

Worry Well: Use constructive worry to help the adolescent, who is often focused on the present, learn to think ahead. Although a burden that increases as adolescents push for more worldly experience, parental worry can have preparatory value. It’s not dampening adolescent pleasure or dooming his future to forecast possible problems or dangers. Parental worry slows the young person down long enough to think beyond the power of immediate pleasure to consider complications that might arise. The parental condition on considering some new freedom needs to be that before permission is considered, there will be some discussion of “what if?” and “just suppose?” questions. Included are ideas for coping in case the unwanted occurs. “Just suppose the people you’re going to the party with start getting really drunk or high, how do you plan to take care of yourself?”

Provide Family Structure: Create a system of demands and limits that foster responsibility and provide safety which the adolescent can depend upon. Just because the freedom loving adolescent resists and resents the constraints and demands of family structure doesn’t mean he doesn’t need, and even want them. At an age when the teenager understands parents can’t make or him or stop him without his cooperation, he knows he follows his own choices, not his parents. This is why he protests the rules of family structure, but mostly consents to go along with them anyway. He has more freedom than he knows how to handle and knows it. So parents get criticized for being “over protective” by a teenager who is secretly relieved the protection is there. His parents know this too: “Our unpopular job is to give him a cage of rules and restraints to rattle around in as he grows, and to take complaints for our efforts.”

Support Speaking-Up: Welcome spoken declaration (even argument) because it is self-expressive and practices having one’s say. The adolescent who shies away from speaking up to parents is also unlikely to speak up to other adults, and even to peers, unable to declare wants, set limits, enter into disagreements, stand up for personal beliefs, and promote themselves. Highly authoritarian parents who act like a child and adolescent should be seen but not heard are doing that young person no favor. At last graduating from their care, her habit of shutting up can hold her back from negotiating her way through the world where adults must be routinely dealt with. Speaking up is an all-purpose socially assertive skill. Just as our Constitution protects freedom of speech; at home with their adolescent parents should encourage freely and respectfully speaking up.

Teach Accountability: Allow the adolescent to understand that when it comes to freedom, all choices come with baggage called “consequences.” By owning that choice/connection, personal responsibility is taught. When parents intervene between a poor adolescent choice and an unhappy consequence, learning a valuable lesson from hard life experience is lost, perhaps putting off that education until another day, saving the young person from learning the hard way. So much of adolescent preparation is from mistake-based education, from trial and error experience. Often painful to profit from, there can be positive lasting effect. “I learned this much: I’ll never do that again!”

Offer Self-Disclosure: Let yourself be known so the adolescent can profit from your life experience. What parents fundamentally give their adolescent is who and how they are. Similarity Connections can be opportunities for self-disclosure. “Sometimes you are like me I think,” explained a parent to his teenager, “I can get easily frustrated and tempted to say things I later regret. I’ve had to struggle with this. For what they’re worth, here are a few strategies I use to keep myself from popping off.” Event Sharing can be an opportunity for self-disclosure. So when a parent loses a job, she describes to her teenagers how this happened, the need to lower living expenses, and how she is proceeding to look for a new position. Now the adolescent is learning from a parent how to cope with and recover from sudden unemployment, a very common life experience. Particularly powerful can be parents Self-disclosing Mistakes they made growing up. Adolescents can profit from hard parental experience. “Because my Dad drank and drove in college and got badly hurt, I never mix drinking and driving myself.”

Model What You Want: Use treatment you give to encourage the treatment you want from your adolescent. “I’m a salesman,” explained a dad. “I try to treat my family with all the consideration and courtesy I give my customers, and then some more because my family is who I love.” Parents provide primary models for how to act in relationships. Every interaction a parent has with his teenagers is an instructive example of treatment he expects and encourages in return. To the bad can be a parent who yells at the teenager to stop yelling and so encourages the very behavior he wants to stop. To influence change in your adolescent’s behavior, sometimes what it takes is changing your own. To the good can be a parent who is calm and reasoned in conflict from whom the adolescent, when in disagreement, learns to act the same. Conflict can create resemblance: in this case, the teenager comes to imitate conduct his mother has shown.

Parenting practices are choices. Parenting is a very creative, improvisational, and resourceful process as responsible adults strive to maintain a relevant connection with an adolescent undergoing rapid growth. This always makes me mindful of that old IBM slogan: "the future is a moving target." In parenting, so is adolescence, when parents have to constantly keep adjusting their perception as the process of developmental change unfolds. It’s easy for parents to feel at a loss, stalled and stuck, at points during this complicated passage, which is what can make supportive gatherings of parents helpful. Suggestions and ideas from other parents can inspire fresh approaches and strengthen resolve.

As a closing example, consider a practice a mother contributed at a recent gathering. At issue was how to respond to her middle school son’s persistent attempts at delay— “I will in a minute,” “I promise to do it later,” “You’ve already told me!” How could she encourage more timely cooperation? “Active waiting” was her solution. She described it like this.

“When I ask for something to be done, I don’t allow more than a five minute delay. So if he’s escaped with a promise into his room and closed the door, I just knock and walk in with a friendly smile on my face and stand right beside where he’s sitting or lying down. He doesn’t welcome my company, but I just keep giving him my cheerful smile without saying a word. “Mom!” he grumbles. “What are you doing here, why are you standing there looking at me like that?” “I’m just waiting,” I smile in reply. “For what?” he asks. “For you to do what I asked,” I explain in a friendly voice. “I said I’d get to it in a minute!” he complains. “That’s fine,” I answer. “I’ll just wait wherever you are until you do.”

Now I was curious. “That’s it? That’s ‘active waiting?’” “Yes,” she smiled. “And it usually works like a charm.”

So I added another possible positive parenting practice to my list.

For more about parenting adolescents, see my book, “SURVIVING YOUR CHILD’S ADOLESCENCE (Wiley, 2013.) Information at: www.carlpickhardt.com (link is external)

Next week's entry: When Parents Name-call their Adolescent

No comments:

Post a Comment